- Home

- Suzanne Palmer

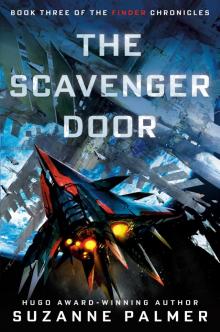

The Scavenger Door

The Scavenger Door Read online

DAW BOOKS PROUDLY PRESENTS SUZANNE PALMER’S FINDER CHRONICLES

Finder

Driving the Deep

The Scavenger Door

Copyright © 2021 by Suzanne Palmer.

All Rights Reserved.

Jacket art by Kekai Kotaki.

Jacket design by Adam Auerbach.

Interior design by Alissa Rose Theodor.

Edited by Katie Hoffman.

DAW Book Collectors No. 1883.

Published by DAW Books, Inc.

1745 Broadway, New York, NY 10019.

All characters and events in this book are fictitious.

Any resemblance to persons living or dead is strictly coincidental.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book via the Internet or any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal, and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage the electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated.

Ebook ISBN: 9780756415167

DAW TRADEMARK REGISTERED

U.S. PAT. AND TM. OFF. AND FOREIGN COUNTRIES

—MARCA REGISTRADA

HECHO EN U.S.A.

PRINTED IN THE U.S.A.

pid_prh_5.7.1_c0_r0

To Kelly, who showed me it was possible to live in this world on your own terms.

Contents

Cover

Also by Suzanne Palmer

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Chapter 1

“Neptune smells,” Fergus Ferguson said.

His sister Isla was slouched low on the worn, brown sofa in the tiny, cluttered apartment above the Drowned Lad, a lightball on dim hovering overhead. She glanced up from her handpad, pushed away a lock of red hair from her face, and scowled at him. “What?” she said.

“I said Neptune smells. It’s the damnedest thing,” he said. He was perched on an old oak stool, one leg mysteriously a centimeter shorter than the others so that it wobbled every time he took a breath, his chin in his hand and elbow on the kitchenette’s island. “I mean, there’s nothing particularly exceptional about the atmosphere, and it’s so cold everything is frozen, but when you get back from any kind of out-of-ship activity, your exosuit smells. It can take weeks to fade.”

“I asked—five minutes ago, mind—if ye knew how to calculate the proper speed and insertion angle for a standard Cricket-class cargo ship carrying five tons of liquid water to land on one of the wind-cities of Neptune,” she said. “Not how it smells.”

Fergus shrugged. “No one would do that. They’d let the water freeze so its mass distribution is stable. Keeping it liquid would burn a lot of energy and make the whole process harder.”

“I’m sure the exam proctors would be entirely happy to give me full credit for writing in This is dumb and also Neptune smells instead of doing the actual math they asked for,” Isla said. “I am trying to study here. Don’t ye have something else to do?”

“At the moment, no. Gavin kicked me out of the bar.”

“Big surprise there. It’s probably the ammonium sulfide.”

“What?”

“The reason why Neptune smells,” Isla said. “Honestly, don’t ye know anything at all?”

He got up from the stool, stretched his lower back, and looked around the tiny apartment. “Discovering I have a little sister I never knew about has been fantastic,” he said. “It makes me feel so loved and appreciated.”

“If ye want to be appreciated, go down to the bar and grab me some chips, then,” she said, and looked up again long enough to give him a very big, very insincere smile. “Take as much time as ye need.”

At least it was something to do, besides sitting there trapped by his own desperate need to make himself useful to people who had no use for him, however much they all tried to pretend otherwise.

Chips it was, then. He went down the narrow back stairs to the bar kitchen. It was Friday but still early yet, and the Drowned Lad’s cook, Ian, was leaning against a counter, staring off into something imaginary behind an opaque pair of movie goggles, utterly unaware of anything around him. Fergus had questioned Gavin’s sanity for sticking with the old-fashioned kitchen gear, but it hadn’t taken long for him to admit that his cousin’s way made for much tastier food. At least when Ian didn’t let it burn; there was a basket of chips down in the oil that was already well past golden and heading toward greasy charcoal; Fergus lifted the basket out to drain, and Ian turned off his glasses.

“Oh, hey, Ferg. Didn’t hear ye come down. Help yerself,” Ian said, then caught a look at the cooling basket and winced. “Oh. I’ll start more. Give me a few?”

“Sure,” Fergus said.

Against Gavin’s earlier injunction, he went back out into the bar. His cousin was pulling glasses out of the autowash behind the counter and stacking them back in the shelves. He looked up when Fergus walked in, sighed, and went back to his task. “I could help with that,” Fergus said.

“Done now,” Gavin said. He closed the autowash door and leaned back against the back wall, with its display of bottles. “That didn’t take long for her to kick ye out, too.”

“Yeah,” Fergus said. “Apparently, she doesn’t want to know how Neptune smells.”

Gavin snorted. “Kids these days,” he said.

There were only a few people in the bar, though that would change once the rainy April gloom outside settled into the more-comfortable full dark of night. Fergus had been there for a little under two weeks now, trying to assimilate the fact that he had a little sister, born after he’d run off to Mars at fifteen and never looked back. He didn’t know where he belonged anymore. If he and his cousin hadn’t looked like they could be twins with their matching red beards, no one would ever believe he was even from there. His speech had long since drifted into more Mars than Scotland, more offworlder than Earth.

“This is her last exam, then she’ll head back to our folks’ place for break,” Gavin said. Fergus’s aunt and uncle had raised Isla, having realized after Fergus’s departure just how badly his mother couldn’t. And now his mother was gone too, years past, and it was both a guilty relief and a lingering, painful recognition that now nothing ever would be resolved, made amends for, or even understood.

“Sorry,” Fergus said. “I don’t mean to get in everyone’s way.”

“That’s not it at all,” Gavin said. “But I’ve been meaning to have a word or two with ye about it. Sit.” He pointed to an empty stool at the bar.

Fergus sat. Gavin gestured toward a bottle of scotch on the counter, but he shook his head. He’d never been much of a drinker—except for a few occasions when he spectacularly was—but he had reasons now to need to stay in control. At least in that respect, Scotland so far had been good for him, no uns

ettled rumbling of electric, alien bees in his gut to add to his unease.

Gavin poured them both water instead.

“Ye came back, and yer full of tales of Mars, and Saturn, and places so far away I can hardly imagine them. And all yer tales are full of people and aliens and running around, doing dangerous stuff. Ye make it all sound like the best fun, but I saw that scar on yer leg and more than a few others like it. And yer ear . . .”

“Some bastard cut it off,” Fergus said. He resisted the temptation to reach up and touch the replacement. “It’s a new grow. The cells take a while to figure out how to look natural.”

“That’s the thing. Ye say ‘someone cut my ear off’ like I’d say I just bought a pint o’ milk down at Dougal’s. Sitting around, doing normal, boring stuff isn’t yer game, Fergus.”

“Not really, no,” he admitted. “But I’m trying to learn.”

“Well, I have a reprieve for ye. A job,” Gavin said. “Ye said ye find things for a living, so I’ve got a friend that needs something found. Should only take ye a day or two, and ye’ll be back before Isla heads off. It’ll be good for ye.”

Ian came out of the back and sheepishly set down a bowl of chips in front of Fergus before scuttling quickly back into the kitchen. This batch wasn’t any less burnt than the last.

Gavin closed his eyes for a second, took a deep breath, then opened them again. “Besides,” he said. “Isla will bankrupt me on chips alone if she doesn’t have to get up and fetch them herself. What do ye think?”

It did sound good, and more than that, it grabbed his curiosity. Fergus had tracked down stolen spaceships, missing art, historic relics, and kidnapped people, all across the galaxy, but he hadn’t expected to find any need of his skills here. What rare, interesting, possibly priceless thing had gone missing that he could go find?

“Okay, then,” he said. “I’m in. What is it?”

“My friend Duff,” Gavin said. “He’s lost one of his flocks out in the hills.”

“. . . Sheep?” Fergus asked.

“Sheep,” Gavin confirmed. He smiled. “After closing tonight, I’ll help you pack.”

* * *

—

Duff was one of those men who’d grown into a classic maritime face as he’d gotten older, the lines of it challenging the rocky coastline for title of craggiest topology. When he smiled, it was like watching a rockfall in reverse. “Mr. Ferguson!” he said, and held out his left hand for an awkward shake. His right arm was bound up in a smart cast. “Slipped on th’ ice,” he said. “Three weeks afair ah can drive or dae much at aw. Bad timin’; mah dug died a month ago.”

On the way up to Duff’s place, first by train, then in an auto-taxi, Fergus had come up with a dozen reasons he couldn’t go looking for this man’s sheep, and almost another dozen ways the man could try to find them himself. Now he swallowed all those suggestions and stood next to Duff, looking out into the distant hills that were capped in white, leftovers of a late spring storm three days earlier. “How many?”

“Twintie-two,” Duff said. “Mah nephew left th’ gate open in th’ storm. Ozzie—she’s mah bellwether—has a pinger on ’er, but th’ signal’s bad out thaur. Ah’d drive around until ah pick it up, but ah cannae.”

Duff handed over a scanner that was so old, it looked like it could date back to the twenty-third century. “Ye got guid boots, thick soles?”

“I do,” Fergus said, though they were loaners from Gavin. As were the pop-shelter, his gloves, and, honestly, most of his clothes. When he’d arrived on Earth, he hadn’t been planning on staying more than a few hours.

“Guid. There’s some sharp debris up thaur, cam doon ten years ago after some orbital accident. Government cam and cleaned up th’ big pieces, but still ye don’t want to be running around in yer baur feet. Plus all th’ sheep jobby, of course.”

“Of course,” Fergus said.

“Gavin says yer his cousin? Moira and Ranal’s lad?”

“Yeah,” he said. “I’ve been away for a long time.”

“Soonds like you’ve ne’er bin here at aw, th’ way ye gab,” Duff said. “A’ folk said ye drowned in th’ new sea.”

“Yeah, I heard that,” Fergus answered. He’d only recently learned that was what his mother had told everyone after he’d left. It was an easy lie, because those same waters had claimed his father only a month earlier. “I went to Mars.”

“Mars, eh? Well,” Duff said. He seemed to ponder a few moments, staring off at the hills where somewhere, his sheep were hiding. “Gavin gonnae change th’ name ay his bar, then?”

“Not that I know of.”

Duff gave a lopsided, one-shouldered shrug. “Ah packed ye a poke ay things ye might need,” he said, and gestured to a bag on his porch. “There’s flares, if ye need help. Ye hae some skill with herding?”

As Gavin had said before sending him out the door that morning, Fergus’s chief qualification for finding the missing flock was being better at getting himself lost than anyone or anything else. Just think like a sheep, Gavin had advised.

“I’ll find them,” he said. “After that, we’ll see.”

“If ye can gie Ozzie tae follow ye, ye should be braw,” Duff said. “Ah’m grateful for yer help.”

“No problem,” Fergus said. He picked up the bag and his pack. Behind Duff’s small farmhouse was the barn, and past that, the fence with its far gate still open. The hills, dotted with patches of snow, rose up behind it all. “Any idea which way they went?”

“Up,” Duff said, and Fergus figured that was exactly his luck. He dismissed the auto-taxi, shook hands one more time with Duff, and headed out.

Duff’s farm was on the northwest side of the peninsula that had formed when the rising waters had flooded the narrow land bridge between Lochs Long and Lomond. The wind wasn’t unbearable, though Fergus did have to admit that his scale of what could be borne might be badly askew; the last windy stretch he’d crossed had been about fifty meters between two halves of Huygens Settlement on Titan, when the winds were a mild sixty kph and the temps a balmy -168 C. If Scotland felt colder, it was all just in his mind.

It took him about two hours to reach the first bluff, the snow not yet wholly covering the ground or hampering movement. He settled down on a patch of thin grass and pulled his water bottle out of his pack. After a long swig, he set it down and switched it on so it could filter more water from the atmosphere to refill. In Scotland, that shouldn’t take long; on Mars, it would have been hopeless folly.

The sun was out and bright, and he wasn’t being hunted, wasn’t running to or from anywhere, to or from anyone. There were definitely worse places to be, and he’d been to many of them. He took out Duff’s tracker, pulled out his handpad—bought new in the Sovereign City of New York two weeks before, his last one a melted, crushed ruin somewhere deep under the ice of Enceladus—and synced them.

The handpad had better range than the tracker, which he tucked safely back in his pack, but it wasn’t picking up anything yet. Somewhere a drone buzzed, too far to see, just on the edge of his hearing, but otherwise, it was just him and the hillside and a ridiculous job. He took a deep breath of the crisp, fresh air and resumed his hike.

When he reached the snowline, he moved laterally along it as best he could over the rocks, until he found the unmistakable signs—visual and olfactory—that a large group of animals had moved past.

Fergus followed.

He found a patch where the sheep had dug through the snow to the sparse grass and clearly had spent some time before moving on. He found another rock and sat, had a snack and some more water, and looked down across the hills, valley, and loch below. He kept waiting for it to feel like home, for him to feel like he belonged there, but it didn’t come. Instead, his thoughts drifted to the Shipyard in Pluto’s orbit, and his accidental cat, Mister Feefs, rescued from Enceladus and now safe in

the care of Effie and his other friends. The cat was smart enough to remind someone if he needed feeding, right? He hoped so, anyway. He had never had a cat before, and the sense of responsibility for it—especially from afar—was an odd and unfamiliar encumbrance.

He had a small room of his own in the Shipyard, with a few of his things, and he missed it suddenly and terribly.

Picking up his bottle, he took one last look down toward Duff’s farm, now a tiny toy-sized set of scattered blocks, and saw something glinting in the sun not far back down the slope. He left his pack and bottle and trudged down through the churned-up snow.

It was a small, nickel-colored shard of metal. He turned it over in his glove, noting the unusual fracture patterns along the edge, and the fact that a decade or more out in the weather hadn’t dimmed its sheen. The alloy didn’t look familiar, but then, he wasn’t an expert. He stuck it in his pocket, thinking he’d show it to Theo, the Shipyard’s physical engineer, before remembering that Theo was most of a solar system away.

I don’t know how long I can stay here, he thought. He also didn’t know how he could leave again. He’d come back to break his last, lingering, tenuous tie to this place, and instead found himself unexpectedly fastened down more strongly than ever.

At least he had something to do. He gathered up his things and headed uphill again, after the trail.

Late afternoon, as the sun was starting to settle down below the hills and cast a brilliant orange glow over the snow and against the patchy clouds spreading out overhead, his handpad picked up a faint trace of the tracker at last. It was nearly night when he caught the first sounds of sheep drifting down over the hillside, and by the time he was among them, the dark had rendered the rocky hills treacherous.

He took a bag of carrot sticks out of his pack, dropped a few in a can, and rattled them around until he was surrounded by a sea of dirty off-white. One by one he bribed the sheep, until at last the fattest, wooliest one came up for her share, the red collar and bell and tiny blinking red light of the pingtracer barely visible among her fluff. “Ozzie,” he greeted her, and gave her two. “Tomorrow we go home, okay?”

Surf

Surf The Scavenger Door

The Scavenger Door Finder

Finder